Value Investing for Comms: Go All-In on Principles

Leaders invest in a lifelong portfolio of principles, stories and proofs for their comms. Chronic underinvestment in principles is your advantage, as Buffett's own approach to comms shows.

Warren Buffett's investment strategy is famously simple: find undervalued companies and hold for the long term. His communication strategy is equally powerful and much easier to copy.

His approach solves the one major paradox that makes being a leader feel like a no-win situation.

You need to repeat key messages consistently to be effective

You can't sound rehearsed if you want to be seen as authentic

Leaders are like lovers: it’s always easy to say something beautiful at the start, but saying the same thing every month of every year feels stale, yet saying anything else, OR not saying, can seem like a betrayal.

Most managers solve this by creating entirely new presentations for each audience. This is exhausting and ultimately ineffective. I remember a poor manager of mine that I loaded with exciting new speeches for every presentation they gave, thinking I was doing them a favor. At a certain point he asked if I could please just re-use material. It wasn’t that they disliked the speeches, they said. But they felt like a pop band always doing cover versions. I’d forced them into becoming the Mili Vanilli of executive presence.

Buffett takes a different approach – one I call the 50-40-10 Formula in terms of how you should invest your creativity when crafting any given presentation.

50% Principles: Memorable one-liners that are uniquely yours and drive action. They’re flexible enough to stay true over time and apply to many situations.

40% Stories: Personal narratives about individuals that evoke genuine emotion

10% Proofs: Key data points that create belief and validate your message

Why am I so bullish on principles? They stay true for a long time and can be applied to a lot of different contexts and stories without diminishing in value. In fact, you will find that the more you focus on principles, the easier every subsequent speech becomes. It explains why Buffett can repeat the same core ideas year after year without ever sounding stale.

How Buffett Makes It Work

Analyzing his 1977 letter to shareholders reveals his technique, although this analysis basically holds true of every letter of his I’ve run this analysis on. I’ve only picked 1977 because it was a great year for giving birth to people.

Principles That Stick

Buffett crafts statements that make you smarter just by remembering them:

"Insurance companies offer standardized policies which can be copied by anyone. Their only products are promises."

"One lesson we've learned – and unfortunately sometimes re-learned – is the importance of being in businesses where tailwinds prevail rather than headwinds."

These principles create mental frameworks that continue working long after the letter is put down and the meeting ends.

I had a manager who was always noting down these phrases when he heard them, and was always citing his father’s principles when explaining what the team had to do. His father was amazingly wise and surprisingly relevant to Google comms. It later turned out, the manager confessed to me that he simply used his father as a way to combine compelling stories with principles. I have to say, I felt a sense of betrayal, but I remember everything that that manager’s father didn’t say to this day. I salute you, Imaginary Mr. Nelson, tech visionary of 1960s Boston!

Stories That Connect

Hopefully, you will remember that story as a way to see how principles create memories. Buffett is always reaching for a story. Rather than drowning readers in figures, Buffett turns facts into human narratives:

"Gene Abegg formed the bank in 1931 with $250,000. In its first full year, earnings amounted to $8,782 Earnings in 1977 amounted to $3.6 million, more than achieved by many banks two or three times its size.... Late last year Gene, now 80 and still running a banking operation without peer, asked that a successor be brought in."

Or

Management also has been energetic and straightforward in its approach to our textile problems. In particular, Ken Chace's efforts after the change in corporate control took place in 1965 generated capital from the textile division needed to finance the acquisition and expansion of our profitable insurance operation.

Notice how in both cases he looks for a person, any person really, to humanize a fairly dry story of return on equity.

Proofs That Convince

Buffett uses data sparingly but effectively, making numbers meaningful through context:

"No additional shares of Berkshire Hathaway stock have been issued to achieve this growth. Rather, this almost 600% increase has been achieved through large gains in National Indemnity's traditional liability areas plus the starting of new companies."

How it all adds up

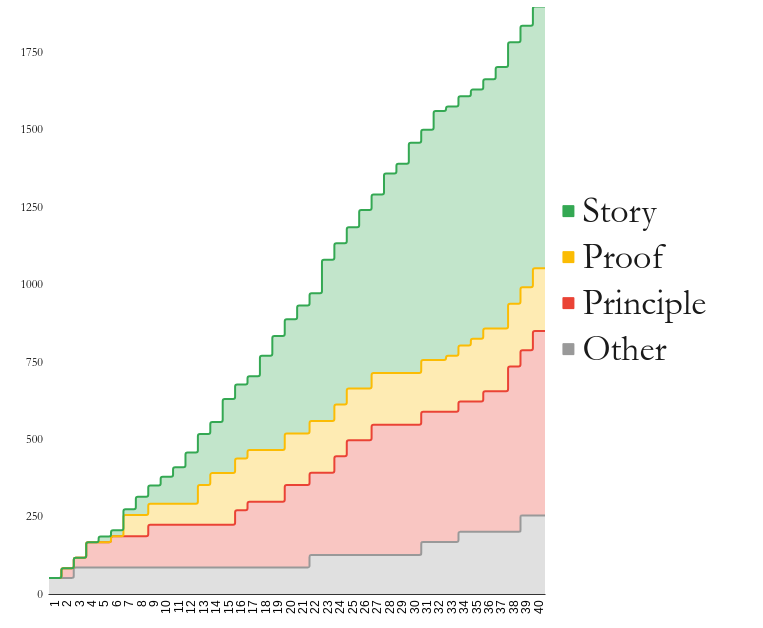

Here’s how the word count of these elements adds up across his entire 1977 letter to investors:

Notice how few words he wastes on data points and proof.

If over 20% of your speech or newsletter is data or proof, you’ve got to readjust your portfolio.

Try This Today: Your Leadership Communication Makeover

Audit your last presentation. What percentage was principles vs. stories vs. proof?

Create your principle bank. Write down 3-5 core insights that guide your decision-making after you’ve collected your data and before you do your preso.

Collect your stories. Identify experiences that demonstrate your principles in action. The sharper your personal principles, the more stories you collect. A chance encounter on the way to your talk becomes your opentiong anecdote.

Prepare your next talk using the 50-40-10 ratio. This is not to say that you should skimp on data, and in fact in many presentations your audience might demand pages and pages of it. The key thing is that wherever possible, you should work to make the data feel like a story and connect it to a master principle.

Instead of starting from scratch for your next presentation, try recombining your principles, stories, and proofs from the previous one for this audience.

Just like Taco Bell creates an entire menu from essentially five ingredients, you can create seemingly unlimited communication variations from a carefully curated set of principles, stories, and proofs.

What would change if you spent less time creating new content and more time perfecting your core message?

In upcoming newsletters, we'll explore each element of the 50-40-10 Formula in depth, including how to craft unforgettable principles, transform data into stories, and select the most powerful proofs for your message.